While I may have always been interested in clothing (especially vintage) in some capacity throughout my life, it was my interest (and obsession) with music that taught me how to pay attention to expression, story telling, and ultimately developing a style. It was through constant analysis (in a hobbyist capacity) and introspection that I helped form my taste, which I later got to express not simply by showing people my favorite pieces but by writing my own music that put it all together. It’s no surprise that my enjoyment of clothing manifests itself in a similar fashion [lol].

I know it’s always a stretch to try and talk about both topics simultaneously on this blog, considering I am an enthusiast at best (I did not go to any type of art or fashion school), but they are quite important to me. It seems that I’m simply interested in expression and style. And it is the latter that brings me to write this blog post today.

No one asked for this (especially as I said that I would try to talk about “soft” topics after last year’s big one), but I’ve been entertaining the idea of writing about style and what it means to express it. I know that this topic is definitely a nebulous one and I’m sure a few people will have their issues with whatever this post ends up being. Here we go anyway!

Discussing “style” is almost always a fools errand due to its reliance on subjectivity, but I do want to share a few thoughts on it, especially as it relates to developing cultural patina, which is the idea (or goal) that certain elements of taste and expression stick with you and develop while still remaining discernable. I hope these thought starters will be interesting and reveal something about how I look at clothes, as well as all other creative endeavors.

When most people talk about style, or more specifically personal style, the discussion usually revolves about being unique as well as being related to being on-trend or part of the zeitgeist. On the surface, this is helpful when separating someone being intentional from someone going through the motions, but since people’s perception of effort can be skewed (and stylish people can often make outfits with ease) and if we consider how elements of classic menswear has made it into the zeitgeist (making loafers and wide leg pants quite common amongst the initiated), “uniqueness” isn’t a good metric for personal style.

I find it much more interesting to talk about intentionality and recurrence. Intention is what brings together knowledge, technique, taste, and POV all together. Recurrence is what codifies it as a part of our style rather than just a one-off. When we view style through this lens, it really becomes about what actions we take that help us achieve our expressive goals. In other words, it’s all about the “how we say it”, and in some cases, “what we do while we’re saying it”.

Perhaps it’s more effective to think of all of this in terms of style moves instead of as a “have it or not” thing. Again, this isn’t meant to be an answer or definition for style, but just a way to think about it!

To me, style moves are the optional actions we take that are based on our taste (or past) and often manifest across what we make (outfits, songs, art, etc). The combination of such moves make up our style. They are things that others may see as arbitrary but to us are an inherent part of our expression.

I’d also like to note that style moves do not have to be there from the beginning of our creative journeys, but they typically show up quite often after we realize our kinship with that move.

I understand that with this mindset, it’s easy to discuss style in terms of bold moves simply because it’s easier to discern and get a sense of what someone is trying to say. But we know that isn’t the only way to have style. Style moves could be as subtle as having a preference in a collar shape or a cut of jean, and the lord knows that there are dozens of variations for both of those things. But yes, they could also be as big as having a hat you like to wear or a signature color (or color combination). But it’s not just about owning or wearing it, but how we do it.

In other words, my view of style isn’t about owning a western fedora hat but taking note of how you wear it. Do you wear it across everything? If no, then what do you wear it with? Is it with generally western outfits or do you pair it with other things? Do you have other hats that you wear? Maybe a tenet of your style isn’t just that you wear a western hat but that you are a hat guy and you enjoy the challenge of finding hats that work with different outfits. Whether it’s specific or a broad move, it’s about recognizing a discernible technique or approach recur throughout different outfits.

I share those rhetorical questions to show that the tenet of my style philosophy isn’t necessarily about owning “interesting” garments but rather to focus on the technique and execution of one’s ideas. Solid brown suits, while an “uncommon” choice for most suit wearers, are still a suit made of a solid color; it’s not as brash as a pinstripe or a check. However, style will manifest in how one wears it, whether it’s done corporate, vintage, or western. It may not be done the same way every time, even within those buckets, but if you introspect, you’ll find a recurring technique that either defines your approach or provides a guide for how you make outfits with that move. And I bet that other people will be able to notice it too.

After all, there is a reason why some outfits and combinations can feel like certain things (formality, shops/brands, specific people). Olive chinos with ivy blazers and tweed feels like something out of a Japanese style magazine (or in this case, Shinn). Wranglers with a ribbed tank and work shirt is very Edgy Albert (or Silverlake or NYC or current menswear zeitgeist). A beanie with a suit and NBs calls ALD to mind (or NYC again lol). A somber plaid jacket, blue striped shirt, grey trousers and suede shoes is Jake Grantham and Anglo-Italian through and through. 70s details like bias edging on lapels and a dramatic cut worn with vibrant shirts and ties is very Mad King George. It’s hard not to think of Ethan Newton and Brycelands when someone wears delicate slippers with hearty selvedge jeans and a vintage-esque jacket. Berets with ivy-adjacent looks is quite Tony Sylvester.

None of these are inherently unique or revolutionary, but it helps codify their styles, at least to an observer. A lot of that is because these people have done these (or similar) moves for a long time, resulting in a bit of cultural patina for them and something clear to discern for us. We can then try to frame our own style with this in mind, figuring out what moves we do and perhaps what moves we can lovingly “take” from others and apply to ourselves.

This Abed-Brain thing might be a little bit crazy, but it’s really how I see not just fashion, but the wider world. I’ll finish this off with a musical example, in order to bring us back to the intro and show just how my interests in composing (both as a listener and creator) have taught me to be discerning of specific moves and how they make up someone’s “style”.

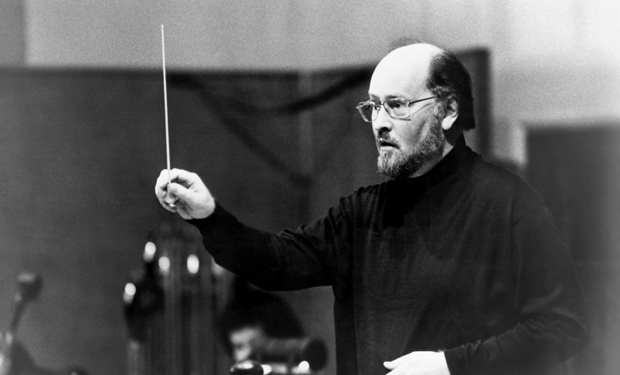

If you aren’t aware already, I am a fan (and amateur scholar) of John Williams’s style of composing. Yes, I am aware that he has a broadly classical “sound” that stands out, especially against the Zimmer world we currently live in. But for me, it’s more than that. After all, there are plenty of movie (and concert) composers today who have or are heavily inspired by the old stuff. No, I am a fan of the specific techniques and style moves that show up frequently in his works. To me, this is what makes up his style.

A lot of media has already been dedicated to analyzing John Williams’s style. This one by by Nahre Sol is a good example of it; she goes into the tell-tale intervals that are found within Williams’s iconic hero and love themes, the harmonizing techniques that are no doubt found in his jazz background, and his adeptness in writing to set the tone and context without being cheesy. Threads in the JWFan site like this and this (which I made lol), are quite similar with a few nuanced details like writing dynamic changes, the use of certain scales, and a few tropes like woodwind runs and frantic strings.

While these are nice dives into my favorite composer, I always found that something was lacking. I found these a bit too surface level as well too specific at times. He’s more than just being a post-Romantic composer who uses a major 6th interval in his love themes; lots of people do that. I wanted something deeper, something that truly gets into the style of John Williams. Something that anyone could hear and immediately know it’s John Williams, similar to how we know that something can look

So I thought I’d try to explain one of the many tenets of John Williams’s writing style that should help illustrate my enjoyment of his music as well as serve as an example of a consistent style move that permeate through his work. And that example is his use of “melody and response”.

In various John Williams’s works, he employs what I’ve called a “call and response”. This is exactly what you think it is: some instruments play a melody and shortly after, other instruments respond to it with a complementary melody.

The Response serves as an “accent” to the main melody, most often used to break up elements of a longer melody (theme) or as a cap to the end of a theme. While the Response can be developed later in the piece as a proper secondary (or “B”) theme , it’s effectively a form of short filigree, seemingly a nice thing to fill up the “air” after the main melody/theme/idea plays. But you’ll find that it’s more than that. It’s a compliment to the main melody, a close friend that is never too far behind. It doesn’t overshadow the main theme yet can be just as hummable.

This might sound weird, but believe me, you’ll be able to notice it! And when you listen to some other composers, you may notice that some of them don’t do it, which makes it much more Williams-y.

To my uneducated brain, this seems to be a bit of a carryover from jazz where instrumental accents after melodies or the end of sung parts are often found. An example of a response can be found in Come Fly With Me immediately after his first line “let’s fly away” (at 0:10). It’s almost as if every sentence ends with some kind of response from the orchestra!

John Williams grew up as a jazz musician so it makes sense that this is a part of his “technique toolbox”. But what makes it interesting is the fact that he employs outside of a jazz-song context, making it a part of his overall composing style. Let’s look at an example (or a few).

The Mission Theme (from NBC News)

Above is a score reduction of The Mission, the concert version of the themes he wrote for The NBC Nightly news. At 0:21 you can hear the lush main theme (marked “Theme B” in the video above), written in the Lydian mode which gives it a “wondrous” vibe, played in the strings.

Almost immediately after the first phrase of this main melody, there is a response by the woodwinds in the form of a descending motif, played staccato. It not only fills the air but adds something to the “world” of the piece, effectively serving as a natural extension of the main melody. This is helped by the Response playing notes within the mode’s scale and therefore reinforces the overall vibe of the piece.

I’ll also point out that the Response tends to play a note twice as it “descends”. I’ve come to call this repetition of a note while going up or down in a melody “double landing”. This is another style move (a subtle one) that can be found in all over John Williams’s compositions…especially in his Responses.

The Olympic Spirit (For the 1988 Olympics)

In The Olympic Spirit, Williams has a rising, heroic fanfare as the main theme. As it reaches its fully fleshed out variation at 2:21, he uses as Response a bit of a vamp, echoing some of the intervals found in the main theme but being different enough to not feel as if he’s just repeating himself. This is a testament to his melodic writing abilities but also to orchestrate and give contrasting melodies to different instruments to prevent things from getting too muddled.

Dobby the House Elf from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

For his theme for Dobby, Williams wrote a meandering-yet-dignified theme for the heroic house elf, which is long enough to be broken up with responses. In the above example at 1:43 the Response involves more notes than the previous examples, being a full run down a scale (in staccato to feel whimsical), played every time the french horn finishes a fragment of the melody. After the woodwinds go twice, he even allows the low strings to do a bit of their own Response.

If you keep listening to 2:05, he does another variation, doing another woodwind Response this time for Dobby’s B theme (played by the low strings). Williams can’t resist doing Responses!

The Belly of The Steel Beast from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

Perhaps my favorite (and perhaps weirdest) example is the one found in the cue The Belly of the Steel Beast. The piece starts with a dark theme played by the low strings, shown uninterrupted in the first screenshot. It turns into a bit of a fugue (a technique with two melodies played simultaneously in counterpoint), but the real magic comes when he foreshadows his Response at 1:10– a simple descending four note “fanfare” played by the trumpets. It’s not

The fanfare-of-sorts doesn’t get used as a Response until 1:24 where it is used to break up the main string melody. Not only does it “keep things interesting” but if you look closely, you’ll note that its almost a mirror to the main theme: the strings seem to meander up and down while the trumpets definitively go down.

The Response also shifts depending on where the main melody is; Williams isn’t just copy and pasting the exact same response. The back-and-forth between the “call and response” is fascinating and quite a delight to my ears. It may also be because the notes of the Response are found within the intervals of the main theme. Genius!

And yes, you’ll notice that this Response utilizes the “double landing” quite a bit!

At the end of this essay, you’ll find a short compilation of other examples of John Williams employing this “style move”. And as you’ll hear, it is apparent that this is simply just a part of his approach to composing, recurring throughout his work across various themes, quirky cues, and action pieces even as his broader style has evolved. He doesn’t use it all the time, as the main themes that most people know for Star Wars, Jurassic Park, and E.T don’t utilize it. Listen to Anakin’s Theme from 0:23-0:48: the main melody plays without any Response or accent. The same goes for his theme for the Terminal. But if you listen to other cues or his wider body of work, you’ll definitely hear it pop up.

Overall, a Response isn’t necessary to write a piece. It’s perfectly fine to have a melody be featured by itself; plenty of songs and orchestral works do that! It’s the fact that Williams chooses to do it across all varieties of pieces that makes me like him. There is just something about how he does it. It never feels lazy; it’s always intentionally done and fresh, specific to the piece it’s in while remaining firmly Williams.

To me, doing a “melody and response” is a part of what it means to be “John Williams”. I can certainly feel it whenever it pops up in his work. And believe me, it’s everywhere. Cultural Patina indeed!

Obviously, this composing move is not a new thing. I am sure an actual music scholar or film bro will be able to give me plenty of examples of similar moves from other composers of film and the concert hall (though in my my experience not many people do this). But that’s okay, because this isn’t about being unique. This is about a tangible move that is consistently found in one’s creative output. A recurring motif not necessarily in the concrete, but in the abstract— in mindset. To me, this is where personal style lies!

I’ve incorporated my own approach to “melody and response” in my own composing. Once you hear it, you’ll never be able to unhear it. As I look back, it’s definitely a nod to Williams, but it’s more than just copying. It’s just something I identify and feel kinship with. And I’ve found it’s the same way with clothes: this whole hobby is about finding moves (garments and how we wear them) in a cognizant way that feels personal to us and characterizes our approach to wearing clothes.

Ultimately, framing the discussion (as it relates to cultural patina) in this way makes “style” more than just being bold/unique or simply as being a part of a broad genre (such as ivy). Yes, those things help us form our mindsets and have conversations (both internally and externally) providing us with context and vocabulary, but style really is more about how we achieve being bold or even being ivy.

When we look at the latter for example, there is definitely a hard uniform of what we expect from a trad, but there are still different ways to express it, especially when no one is saying that we are obligated to do the look exactly as it was in the hey-day. I’ve done nods to ivy with spearpoints and pleated trousers, which go against the button-down collar and flat-front mandate. And I’ve stuck with those choices, which makes it a part of my style’s interpretation of ivy (because I’m not really a true trad, am I?).

Of course that is one example of many that makes up what I’d consider to be “Ethan Style”, just like how MJ and Spencer have theirs. All three of us could all dress “ivy” and still have a different end product, much like how John Williams or Alan Silvestri can write in a “classical” way but still produce a different cue. We all have our own toolbox of details, techniques, and filigree that we use whenever we create something, be it an outfit or a song. With clothing, the style shows up in curation (what we buy, as we don’t just buy everything) and how we wear it.

Also in most cases, personal style comes with some element of copying, at least when you start out. This isn’t a bad thing since we have to get inspiration from somewhere! The whole thing is about knowing what to copy/take inspiration from. A big portion of this blog has been about distilling style into distinct moves as an exercise in expression. The way we get around copying is that we’re supposed to mix and match what we like; the challenge (a fun one) is to figure out how to make it work naturally. Our personal approach and use of curation (or taste) based on true enjoyment of a technique or detail that isn’t primarily focused on external benefits is what makes it authentic. Maybe this is a hot take (or not applicable to everyone) but having a style is about giving a nod to the things we like.

That’s why this isn’t about having a unique style but simply recognizing what comprises your style. Menswear as a Hobby will always be an exercise in introspection. And yes, style will always be a nebulous topic, but I think it is worth thinking about, as this helps us discern exactly what moves we are doing and perhaps what moves we want to make. Because for those of us with Menswear Sickness, all of this is more than just dressing “nice”; the game is always in the details, both in our garments and our execution!

I want to make it clear that I don’t think that intentionality and recurrence is the “make or break” in being the defining part of style. There is a lot that goes into style that is still impossible or not-worth trying to define for fear of being too dogmatic. This whole thing is to help us think about our own style and how to hone our expressive techniques rather than simply evaluate/judge others on if they have “style” or not.

I believe everyone has some sort of style (must like taste) because we all take conscious, discernable actions when we put clothes together. This is especially those of us who like the challenge of making outfits. This doesn’t make fashion enthusiasts better, but rather that they are trying to cultivate and use their style in their expressive journeys.

Discussing style and its components is not a bloodsport in finding out who has more than the other. Instead, it is an invitation for introspection! It should be a pursuit of a deeper understanding of ourselves, our expressive goals, and how we go about it. Maybe I’m alone in this, but I’m definitely interested in finding out what gets to stick with me as I get older and develop Cultural Patina. Because it’s not just a particular garment, but guidelines, moves, and mindsets that we can discern and apply (or discover) for ourselves!

End of essay!

More Williams Examples:

- Liberty Fanfare (for the Statue of Liberty Bicentennial)

- Listen: 1:59-2:16

- Melody: A warm, reserved theme in the strings (labeled Theme C in the video)

- Response: A patriotic woodwind fanfare that shows up earlier in the piece (labeled Theme B)

- Call of The Champions (for the 2002 Winter Olympics)

- Listen: 0:10-3:30

- Melody: A regal theme played by the horns

- Response: A fanfare run in the trumpets that adds to the celebratory nature and vibe of the piece.

- The treatment here is quite similar to the Liberty Fanfare.

- Parade of the Slave Children (The Temple of Doom)

- Listen: 0:22-0:46

- Melody: A heroic Lawrence of Arabia-esque theme played by the strings and low horns.

- Response: A jaunty motif played by woodwinds and glockenspiel, which reminds us that this represents the children enslaved by the cult. It’s actually the first theme you hear in the piece (at 0:12). I love that bit of foreshadowing!

- End Credits (The Temple of Doom)

- Listen: 0:36-0:48

- Melody: Indy’s Iconic B Theme in the horns and strings.

- Response: Short Round’s Theme, which is an upward and childish heroic theme played in the high strings, woodwinds, and glockenspiel. It’s most likely used here to show the connection between Short Round and Indy.

- You can compare this to the regular Raider’s March B Part (0:36) which does not include Short Round’s theme as a response.

- Flying Theme (E.T)

- Listen: 0:32-0:50

- Melody: Iconic Flying Theme played by unison strings.

- Response: Fluttery woodwind runs, accenting each fragment as they descend, providing contrast to the main melody which feels like it climbs ever higher with each fragment.

- The Attack On the House (Home Alone)

- Listen: 2:17-2:32

- Melody: Low trumpet plays the Wet Bandits Theme accompanied by a droning strings

- Response: Oboe plays a repeated figure in between phrases of the melody, like to make things feel bumbling while adding a bit of silly anxiety.

- This uses the “double landing”!

- Hooray for Hollywood (John Williams arrangement)

- Listen: 0:39-0:53

- Melody: The iconic main melody of the song played in strings

- Response: Rhythmic trumpets accenting the chords of the song at the end of the melody

- The Droid Invasion (The Phantom Menace)

- Listen: 0:31-1:00

- Melody: An ominous and militaristic theme played by the low brass.

- Response: While this isn’t a true secondary melody, Williams employs Response techniques similar to Hooray for Hollywood and The Belly of The Steel Beast, first using repeated staccato fanfares, glissando runs in the woodwinds and horns, and accented “double landings” in the xylophone/glockenspiel at the end of each Melody fragment. It first happens at 0:40 and then at 0:50, these Responses multiply in use, playing after almost every note of the Melody.

- Rey’s Theme (The Force Awakens)

- Listen: 0:33-0:47

- Melody: Rey’s main theme played by horns and strings.

- Response: A rhythmic ostinato motif played by high woodwinds. As was the case in Parade of the Slave Children, this ostinato actually opens the piece!

- “Double landing” appears in the ostinato.

- Rescuing Sarah Extended (Jurassic Park: The Lost World)

- Listen: 2:52-3:18

- Melody: A slow, rising minor four-note figure in the brass, signaling the impending danger of the Rex duo. This is based on the “Carnivore” theme heard in the film.

- Response: After every note in the Melody, high strings in unison play a quick melodic run adding frantic pacing to the score. It’s a dark complement to the Carnivore theme, changing notes within the figure each time the Melody rises by a note. In my opinion, the inclusion of the Response makes the whole cue much more interesting than just the brass rising.

- The Lost World (Jurassic Park: The Lost World)

- Listen: 2:15-2:29

- Melody: A rising, adventure theme played by harmonized horns and strings accented by syncopated tambourines.

- Response: Trumpet interjection play throughout, but the true Reponse is a motif played by the woodwinds at 2:20. This motif plays at the end of nearly each Melody fragment until it gets its own time to shine in a fully fleshed out way at 2:36.

- The Response is actually heard earlier in the piece at 0:39.

- Dartmoor, 1912 (War Horse)

- Listen: 1:40-2:06

- Melody: A jaunty theme in the woodwinds that feels very English country.

- Response: Similar to Rescuing Sarah, unison strings in a low register play an upward vamp, though it is a much more positive vibe. It provides much more movement (and interest) than just the repeated pedal note.

- Theme from Sabrina (Sabrina)

- Listen: 2:15-2:37

- Melody: A lush, romantic theme played by the strings.

- Response: It’s a little hard to hear, but at the end of each Melody Fragment, the piano plays a bit of a meandering figure as a Response. It’s built upon the descending scales that are found near the beginning of the piece (0:08).

- Overture To The Oscars

- Listen: 0:25-0:34

- Melody: A grand yet reserved theme played by the low horns and strings.

- Response: A descending motif similar to the one in The Mission, again played by the woodwinds and glockenspiel.

- The Land Race (Far and Away)

- Listen: 3:08-3:26

- Melody: A heroic theme similar to Dartmoor, 1912 played by the strings and horns.

- Response: Staccato fanfare played at the end of each Melody Fragment, making the statement of the Melody feel celebratory.

- Training Montage(Spacecamp)

- Listen: 1:08 – End

- Melody: A rising heroic theme played by synth brass. It’s vaguely similar in construction to The Mission and The Olympic Spirit.

- Response: A short fanfare accent played by synth trumpets at the end of each Melody fragment. This is probably the most unabashedly John Williams Response in the list, almost acting like a Response found in a jazz song while sounding like straight out of Star Wars (which is because it’s eerily similar to the Rebel Fanfare).

- The fanfare heavily features the “double landing”, reinforcing its use as an accent to the main theme.

Ethan Examples

- Halloween March (written in high school)

- Listen: 0:59-1:20

- Melody: A rising, minor theme in the low brass.

- Response: A repetitive vamp utilizing a minor third in the strings and bells, meant to emphasize dread (I hope), that appears after each Melody Fragment.

- Seniors, and We Will Conquer All! (written in high school)

- Listen: 3:09-3:22

- Melody: A march theme in the strings.

- Response: A heraldic accent-fanfare played by the trumpets.

- The Return of Tylar (college):

- Listen: 0:30-0:47

- Melody: A minor theme played by strings, oboes/clarinets and harpsichord.

- Response: A variety of ostinato minor third interjections (flutes) and fanfare “double landings” (horns) played throughout the statement of the main theme.

- Style & Direction for Orchestra (written for the Music essay)

- Listen: 0:16-End

- Melody: A slightly wondrous theme in the Lydian mode played by strings.

- Response: A descending figure accenting each Melody Fragment. Similar to The Mission or Overture To The Oscars.

- Celebrate Graduation (written in high school)

- Listen: 2:05-2:33

- Melody: A harmonized, reserved theme (meant to evoke Pomp & Circumstance) played by strings and horns.

- Response: A fanfare played by woodwinds and glock that repeats three times after each theme statement.

- The Chase Through The Fair (written in high school)

- Listen: 1:29-1:40

- Melody: Appears after the Response! It is a gradually ascending theme in the low woodwinds.

- Response: A repetitive and short descending figure played by strings and woodwinds that accents each Melody Fragment. Note that is makes use of the “double landing”

- The Waves (written for Breathe shortly after college)

- Listen: 0:32- End

- Melody: A slow, pensive and hopeful theme in the piano and synth.

- Response: A descending (and then ascending) figure played by the harp that accents each note of the Melody and evokes the rolling nature of waves at the beach.

- Death of Friend (written for Breathe shortly after college)

- Listen: 0:39-0:54

- Melody: A remorseful melody in the high strings and brass that gradually crescendos as the action happens.

- Response: A quick, repetitive vamp played in unison in the strings meant to evoke hesitation that provides contrast to the pounding tonic notes played by the low strings.

- Isabel on Parade (written as a Christmas 2023 present for Isabel)

- 0:52-1:02

- Melody: A jaunty, staccato theme in the oboe.

- Response: A descending, lithe accent played by flutes.

- 1:13-1:33

- Melody: A long, sauntering and silly theme played by the strings.

- Response: Accents featuring the “double landing” technique played by high woodwinds and glockenspiel for extra effect.

- 0:52-1:02

Thanks for reading! Don’t forget that you can support me (or the podcast) on Patreon to get some extra content and access to our exclusive Discord.

Always a pleasure,

Big thank you to our top tier Patrons (the SaDCast Fanatics), Philip, Shane, Henrik, and Alexander.

5 comments