I’ve mentioned a few times on the blog that I’ve recognized a kinship between music composition and wearing menswear, at least in the way I approach them. I always thought it was surface level, just two things a nerd can hyperfixate on. But as I’ve continued my introspective journey, I think I’ve found that the root between the two lies in an interest in expressing Thematic Development.

I felt like I should speak a bit about how I think about that subject, as it reveals more about how I feel about the fun challenge of making outfits, how it may appear that I seldom “repeat” looks, and how I go about achieving expression in general.

Because while it may seem that this whole blog is always slouching toward some aspect of film costuming (due to the concept of Cinematic Dressing), it’s actually about composing, just with clothes instead of music.

Thematic Development manifests itself best in music. At least that’s how it happened for me.

Humans love recognizing patterns and film score was ripe for it. When I would watch movies (and later listen to the scores), I picked up on the fact that certain melodies were associated with specific characters, objects, and even emotions. As time went on, I started to see the nuances whenever the melodies would recur– these themes would vary and develop based on the narrative and emotional needs of the story while retaining elements of their melodic construction to still be a specific and recognizable theme.

Thematic Variation could happen in one cue or piece; other times the changes would be spread out among multiple pieces. In fact, this exercise and use of dedicated themes that are carried through multiple pieces was a major reason why I enjoyed film score and later classical/concert music, as other genres tend to discard melodies after each song. It didn’t like orchestral music just because it sounded classy, but because there was an approach to the genre that I liked.

That whole thing was incredibly fascinating to me. It wasn’t enough just to be aware of the variations– I had to analyze and catalog exactly what those musical changes were and how they related to the intended expressive effect. This may sound like a chore, but I treated it like a fun game! I was obsessed with the idea of intentionally making a specific melody, keeping its narrative associations consistent while making it a good subject for Development and Variation, as well as the overall idea of using Personal Technique to achieve expression.

As I’ve hinted at in the past, my obsession with these concepts formed how I think about Style and Taste. And just how composers handle Development plays a big part in that, especially the latter.

I’m not really keen on composers who do the bare minimum of the Leitmotif system when composing.

By that I mean that they would craft a melody with specific orchestration and simply copy-and-paste it as needed without altering the instruments or even changing the intervals slightly. An example of this can be found in the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise. When you listen to the score, the main theme (“He’s a Pirate”) plays exactly the same way every time it appears, with barely any development. Zimmer’s suite for Jack Sparrow does indeed have some variation, but again as you listen to the score, whole sections are lifted from the suite and inserted into a cue verbatim.

To me, this method of composing makes thematic material more of a “musical sting” than a theme. To me, a theme needs to be tied to narrative and contain as much expressive nuance as the actors or even the cinematography of the scene (thanks Adorno). As such, it should either be composed in a way that allows for variation or the composer should take care to create variations specific to the narrative need, even if its a small part. Granted, a repeatable sting is “fine” for characters like Jack Sparrow or James Bond, but I find a lack of nuanced development to be uninteresting or mid at best (I’m looking at you, Giacchino).

I’ve also found that I want more from Development, which I know is silly since my obsession and interest for this exercise comes from film scores rather than classical/concert music. I am very aware that plenty of concertos, symphonies, and obviously operas contain multitudes of leitmotifs and general motivic ideas that transform throughout a work, though I tend to prefer ones that are thematic and not an exercise in theory/art. I remember watching Tristain und Isolde and picking up on all the repeated motifs as they arise with their associated character or emotion.

I’m also a huge fan of “La Valse” by Maurice Ravel, which contains various interpolations of a traditional waltz melody. The full piece can be heard HERE, but I like the clip above from The Music Professor since it highlights how Ravel takes a straight foward walts and makes it feel ghostlike and sinister before feeling tender, all through augmenting notes and altering the orchestration. It’s no surprise that people interpret “La Valse” as representing the nostalgia for “old Europe” after it had been devastated in WWI era (though Ravel has denied this). The combination of thematic association and development is such an amazing exercise.

On the flip side, Prokofiev’s “Peter and the Wolf” is not my favorite example of development as most of the melodies are presented the same way each time, though I do like the heroic brass-march variation of Peter’s theme near the end of the piece. However, I like other pieces by Prokfiev, as well as many works from other greats like Copland, Stravinsky, and Walton. But even as I’ve expanded my appreciation and amateur scholarship of classical music, film score is really where my heart lies.

Film score is seen by many as a “lesser” art as it tends to use simplified techniques and is overtly connected to mass/consumerist culture, at least when compared to classical music which is more of a high-art. But I see freedom in that. Film score is still a great playground for technique, style, and exercises in Thematic Development, especially for the composers who do the effort. I find it a place full of “pop”, fun, and intentionality, not unlike my approach of classic menswear.

And that as always brings me to two of my favorite scores that contain not only variation but fun as well!

It goes without saying that John Williams is a master of themes. Just like a production designer creating the tone for a locale or a casting director picking the right actors to portray a character (or even the right extras for a scene), Williams creates thematic material for so many things in a film. His leitmotifs not only represent characters, but locales, objects, and even emotions.

Some appear once and others a multitude of times, all to provide some form of identity in a score; this is what makes it a narrative and not simply background music (a form of defaulting). This could be as obvious as the Force Theme playing not only when someone uses it but as a way to represent Destiny or Fate for the Jedi. But it can also be used for even more abstract things, like a descending, rhythmic Dies Irae-esque melody to represent The Emperor’s Trap, appearing in a subdued version at the beginning of the film (HERE, 2:26-2:34) and then in a frantic, action variation when the trap is actually sprung on the Rebel Fleet (HERE, 1:02-1:59)

Because you see, crafting thematic material is just one half of the job– Williams also takes care to develop his material throughout a narrative.

Williams’s themes could serve as fanfare in one cue, feel lachrymose or lamentful in the next, and jaunty in another. This wasn’t about volume or changing the instruments; Williams takes care to alter the melodic construction itself by changing intervals altering rhythms while still retaining the recognizable identity of the theme. Obviously Williams isn’t the only one who does this, as this blog will briefly show, but there is certainly an approach that I particularly enjoy.

I think this whole thing is best explained by looking at two very iconic themes.

The Indiana Jones “A Theme“

John Williams’s theme for Indiana Jones is one of my favorites, outranking even Star Wars in my personal list. Indy’s A Theme is iconic, being an up reaching melody line played by solo trumpet in the concert suite. What is most interesting about the theme lies in its structure (which you can see in the screenshot above). It’s characterized by upward leaps that repeat a few times, getting higher and higher until the melody resolves into a short fanfare.

I remember hearing a film score analyst say that this structure evokes Indy to a T, as our protagonist improvises constantly and tries and tries again until winning out in the end. Indy’s A Theme is definitely a contrast to the straight forward (aka serious) heroic themes in Superman or Star Wars. Indy is silly but firmly a hero. And not only does this melody work well to represent the adventurous archaeologist, but they also provide a great opportunity for augmentation.

As you can hear in Brad Frey’s video above, the intervals in Indy’s A Theme are incredibly iconic and recognizable. Our ears know that when we hear those specific intervals done in the “right” way, Indy is doing something great or about to win. However, the video above is actually the concert version which is a standalone track and only really appears in the end credits. As such it only contains the main, straightforward uses of Indy’s theme, functioning much like, well, a classical piece composed for the concert hall. We can consider this to be the Correct (or normal) representation of Indy.

What intrigues me most is how Williams takes this A Theme and modifies it for Indy’s narrative story. What happens when the context is different? When emotions change? These Developments are not found in the standalone Theme; instead we need to look at the actual score. And as you’ll notice, it’s not simply a game of copy-and-paste.

Indy’s A Theme appears twice in the above cue (0:48-1:01 and 1:32-1:50)which underscores Indy’s flight to visit Marion Ravenwood in Nepal. You’ll note that the intervals are the same as the “right” way, feeling quite heroic and straight forward. However, this isn’t a copy-and-paste of the Raiders’ March we’ve come to know.

Firstly, we have the orchestration. The theme is played by the woodwinds which already has a “smaller” presence than the typical brass. This variation makes Indy’s thematic identity feel dwarfed and innocent, as if he’s blissfully unaware of the adventure to come.

This is then emphasized by the second point: accompaniment. Instead of a driving march rhythm played in a major key by the strings, horns repeat a minor chord alongside Indy’s A Theme. This figure only plays up the foreboding nature of the cue, as it feels the horns’ death knell will no doubt swallow the woodwinds if not for A theme’s optimistic nature.

The crazy part is that Indy’s A theme is relatively unchanged in its melodic construction. The intervals are the same as they are in the concert version as well as the other heroic stings. It would have been an interesting choice to have simply shifted Indy’s theme to a minor key overall, but perhaps that would have been overkill or simply too expected. Williams instead develops around the theme, simply changing the orchestration and the support, while keeping Indy’s identity largely intact and recognizable. Nuance is the name of the game.

Another example of Williams keeping the A theme intact (no interval changes) while modifying the orchestral backing can be found below at 4:01. Here the A theme plays normally in the trumpets but the orchestra plays a repeated minor rhythm that feels frantic and troubled, as opposed to the foreboding horns in my first example. You’ll also note that this rhythm feels dissonant, almost as if Indy is in the wrong key and needs correction. This repeats a few times until 4:17 where the backing almost makes sense but still feels “off”. It seems that Indy’s troubles are not done yet.

But what happens when we go even deeper and change those iconic intervals?

In the first 10 seconds of the above clip which scores Indy finding a dead end shortly before water explodes behind him, we get our answer.

The A Theme repeats twice, first by high woodwinds followed by horns. But something seems off. The leaping intervals are present, but the notes have been changed, moved around just a bit to give the listener an uneasy feeling. This alteration makes Indy come across sheepish, awkward, and definitely silly.

Williams could have played something silly and non-thematic (not utilizing an existing theme) as to not undermine Dr. Jones but he used the A Theme here anyway. He also could have simply kept the A Theme in its normal state while making jaunty or lightheaded backing, as a flip to my previous example, but that wasn’t done either. Instead, Williams changes the intervals between the notes to create a new vibe, one that is reminiscent of the “right” version but still develops with the scene’s narrative requirement. We know it’s Indy, but something is definitely the matter.

Now that we’ve discussed approaches to intervals as well as orchestral backing, I think its time for bigger example.

I’ll finish the Indy talk with one of my favorite uses of the A theme, which occurs in the “Desert Chase” cue which honestly is more of a musical set piece.

It starts out guns brass blazing, with horns playing a dangerous hunting-esque call, immediately adding tension to the cue. When things calm down at 0:55, we finally hear Indy’s A theme. It’s played by a solo trumpet. It starts out normally, but when it does the second tell-tale leap, the interval is changed. It’s not exactly sheepish, though it does feel unprepared, as if Indy is finding his nerve.

Suddenly at 1:07, we get an explosive, non-thematic brass fanfare which has a small response by a timpani run. Then at 1:17 we are treated to a solo trumpet rendition of Indy’s A Theme again. It does it right this time, though the backing has changed into big blocky brass chords that almost evoke the hunting call at the beginning of the cue, but done in a more heroic and certainly grand treatment.

Indy’s A theme continues again at 1:22 but it’s changed yet again. The intervallic leap is actually higher than normal and the 3-note follow up is certainly augmented and a bit dissonant. It’s not as confident as his Correct theme, but it’s definitely close. Indy seems like he might be out of his depth on this one (as he is one man on a horse chasing an armed caravan), but he is definitely going to try. The “hunting call” plays again to close out this variation of Indy’s theme, but it fits just a bit better here.

And then things return to normal at 1:40, with the solo trumpet playing the normal version of the theme with the iconic march-strings behind it. It pauses briefly for a suspenseful brass interjection when we see the Nazi truck but then continues in full glory at 1:52, now harmonized for a truly heroic presentation, before dropping out for the beginning of the action sequence.

As you can see, even with a heroic moment and money shot, Williams still takes care to add nuance to his compositions. It’s all about getting as much expression from not just the orchestral performance, but how the notes are assembled in the first place!

Of course those aren’t the only examples of Indy’s theme in the cue. Here are more brief examples to jump to, but I suggest you listen to the whole cue in order to get a sense of the narrative and see just how Williams writes.

- 3:07-3:21- This is Indy’s B Theme (which you should recognize even if I didn’t call it out earlier) and its played pretty straightforwardly. It represents Indy getting the upperhand, if however briefly.

- 3:37-3:47- Augmented intervals and played unconfidently with strings in a different key in the background, making Indy sound like he’s present but struggling.

- 3:53-4:01- Indy clearly gets the upper hand here, as the string-backing is now back to “normal” as a march, making the theme sound “right” and confident again.

- 4:38-4:43- A Theme played with normal intervals but the backing signals trouble!

- 7:01-7:09- Indy’s B Theme returns again, but you can tell by the music that something is wrong. The march-strings behind it are in a different key, creating a dissonant sound which is only emphasized by Chromatic Figure brass and woodwind stabs. This continues to feel troubled until…

- 7:30-7:50: The march-strings are back and in the right key, providing the proper lift for the B Theme to take full charge in a truly heroic way. This occurs as Indy regains control of the truck!

- 8:06-8:13- The Correct march strings are back but the horns (not the trumpets) play the A Theme which gives a more mellow (yet determined) vibe to this variation. Indy can now relish in his victory.

Of course, like I said earlier, John Williams is not the only composer who takes care to add nuance and development in a score. That brings me to another John, who takes another interval-heavy theme and twists it in a narrative. You might even say that this score has been developed more than Indy…and is definitely a lot more fun!

The Inspector Gadget Theme (from the Live-Action Adaptation)

The Theme to Inspector Gadget was another one of my favorites. With its clunky and swing-esque minor-key melody, Gadget’s theme calls to mind not only the plodding nature of Grieg’s “In the Hall of The Mountain King” but the “dum “Dum – – – de – DUM – DUM” of the Dragnet theme. For this last part of the blog, I’d like you to pay attention to the melody found at 0:19-0:26, which I consider the main part of Gadget’s Theme. This theme is built on specific intervals, which like Indy’s, is ripe for augmentation. And composer John Debney (not Williams!) did a fantastic job with developing it for the live-action adaptation.

The above is essentially Debney’s updated cover of the original TV theme but like Williams’s Raiders’ March, this piece is only the straightforward version of Gadgets musical identity. In other words, this treatment is what we would consider to be Correct and classic for Gadget. So as always, for examples of nuanced Thematic Development, we need to look at the score proper.

Let’s dive in!

In this cue, which plays during John Brown’s (the future IG) daydream of him saving the day, we are treated to a bombastic and heroic variation of the Gadget theme at 0:18. The intervals are changed slightly to fit a major key and the orchestration is changed from the Opening’s synth-harpsichord and cheesy 90s choir to a symphonic fanfare. It sounds almost like something straight out of Indiana Jones.

This happens again at 0:37, where the intervals are spaced out, giving Gadget a sense of musical grandeur. This larger-than-life vibe comes to a climax at 1:06 where the Gadget Theme becomes a stereotypical march not unlike Williams’s Superman or Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance. This is all done through having fun with intervals, rhythms, and orchestration, which clearly differentiate it from the cartoonish quality from the Opening Titles.

Of course this is all done away with once Gadget snaps out of his daydream. At 1:24, we hear a new variation of the Theme, played now by a solo oboe. Debney plays up the jaunty and domicile attitude with staccato woodwind arpeggios (rising and falling lines) and pizzicato (plucked) strings. This obviously humbles Gadget to the listeners, making him come across normal and earnest. But what is notable is that Debney does this while still representing the musical identity of Inspector Gadget.

Obviously the whole score (and film) is absurd and silly, but you can tell that Debney had a lot of fun composing this work. I’m not going to analyze every cue, so I’ve provided a short list below that should show you the sheer breadth of variation that Debney accomplished with the Gadget Theme. The theme can be jaunty or heroic. It can be lifted directly from the Main Titles (which is essentially a cover of the original TV song) or it can be reskinned for Tango or Big Band. Sometimes we get the theme in full or we hear fragments of it, interjected by brass, strings, or whatever in order to keep each version fresh. The composer’s tool kit of Augmentations, rhythm changes, and orchestral voice swapping are all at play here but it always feels like Gadget. The only difference is the vibe, showing if he’s in trouble, doing something silly, or when he gets the girl. Just listen below:

- Waking Up As Gadget’s use in the story self explanatory– Gadget had a lifesaving operation that turned him into a cyborg. As such, you get his thematic identity at 0:23 which is played by solo flute. The backing is done by a synth bass and other woodwinds, all in a different key which makes things sound “off”, much like Gadget adjusting to his new body; bonus points for combining an “organic” instrument (woodwinds) with machine (synth). This explodes at 0:52 where we get the whole orchestra in the fray, playing a bombastic, polka-esque version of the Gadget Theme, adding to the absurdity.

- Tango, which plays in the background of a fundraiser. You might even consider it a real tango (because it’s done completely seriously) until you hear the Gadget Intervals at 0:55 played by the accordion.

- Swinging Gadget is another interesting variation that takes the iconic Gadget Theme and puts it into a new genre. Just like the Correct Version, Swinging and Tango are in a minor key, which makes it easy to adapt. What fun!

- Fun In The Park has a similar treatment to Polka variation in the previous cue, though this feels more like something out of a 1940’s Looney Tunes mixed with a bit of Sousa. Gadget’s theme is still played in a major key, almost hinting at a heroic future but still completely overtaken by buffoonery.

- New Car/Gadget Takes a Spin is where things get even more interesting. We get the earnest version of Gadget’s Theme at 0:16 played by woodwinds and light rhythmic strings. Then at 1:07 we get the closest version to the classic/Correct Gadget Theme we heard at the beginning. It’s done now in the plodding minor key, played by the brass and backed by a synth drum kit, though the frenetic strings signal danger and inexperience. A fun variation happens at 1:54 where the Gadget theme is augmented, starting normally but never “ending” properly, much like how Gadget is unable to get his car to stop.

- I’m skipping ahead narratively to Rocket Ride which plays when Gadget and Penny rush after Claw. We hear the correct version of Gadget’s Theme here, played quickly by the brass. It feels determined. At 1:01, this changes to a heroic version similar to “John Brown Saves the Day”. This treatment has rhythmic, march-strings behind it which makes a perfect comparison to Indy’s treatment in “Desert Chase. 1:42 brings back the determined minor version, with backing that sounds a bit Loony Tunes-esque yet again before getting heroic/major/march at 2:14.

- I do want to call out some fun changes in interval at 2:30, which sound semi-heroic but still come across as unsure.

- Gadget Saves Brenda is a great cue with a ton of development. After a fanfare not built on Gadget’s theme, we hear him appear at 0:19. This version sounds silly, perhaps the most Looney Tunes/Cartoon-esque than any other cue. You’ll note that the intervals here are definitely changed which when combined with leaping bass line and percussion, make Gadget sound positively wacky. We then get more intervallic augmentations by the brass at 0:31, which musically evoke how Gadget is trying to reach Claw’s helicopter.

- Another intervallic change happens at 0:49 which doesn’t sound wacky but troubled instead, played up by the muted and sliding trumpet.

- 1:57 brings us a determined Gadget with brass playing the correct theme with synth and strings playing quickly as accompaniment as our hero works quickly find stable footing. A similar version occurs at 2:23 with woodwinds and harpsichord again with a broken brass baseline to add unease.

- This all comes to a head at 3:42, where we get a floating intervallic augmentation of Gadget’s Theme played by the strings as he and Brenda glide down on a parachute-umbrella. Woodwinds join in feeling optimistic

- Finally we have Happy Ending. It starts immediately with a heroic augmentation of Gadget’s Theme in brass followed by harmonized woodwinds (which almost sounds like the beginning of Williams’s Superman March). At 0:10, we have a quick major-march version of Gadget’s theme again calling to mind Pomp and Circumstance. Finally at 0:42, Debney treats us to a Disney/Romance variation for Gadget. Note that the intervals, extra notes and additional instruments deviate from the Correct version in order to fit the necessary thematic vibe.

Conclusion

I hope at this point it is clear how much interest I have (and the importance I place) in Thematic Development. It is such a fascinating exercise to have a consistent and recurring identity that still provides room for expressive variation. And as you can tell, this obsession lead to my hobby of composing music, being able to put my beliefs of Style, Technique, and Taste into play.

If you listen to my compositions and especially pay attention to the narrative-driven ones like “The Flight of the Dirigibles”, “The Chase Through The Fair”, and my score to The Chocolate Shop, you’ll see that I love creating a plethora of themes and developing them to fit a story. Though its worth noting that my concert suites I’ve composed for Isabel or my Animal Crossing island, much like the correct Raiders’ March, do contain a fair bit of development, even if it’s doesn’t contain as much nuance as a full musical “story” (concert suites are presentations of a straightforward musical idea after all).

Of course, as we know, my interest in exercising expression led me to find additional avenues to partake in, namely in menswear. And as you can tell from this blog post, this drive for Thematic Development contributed heavily to my approach to getting dressed.

That’s why I think it’s important to become a Learned Listener and develop an analytical approach. Not to be smarty pants, but to hone your expressive execution. Taking apart film scores, especially ones from Williams, and listening to all the various Themes and Variations was especially important in that regard. It wasn’t just me who did this.

As I shared above, Tufts professor Frank Lehman actually did the work and created an extensive catalog of all the thematic material of the Star Wars Saga, which includes analyses for the various melodic augmentations and orchestration changes that Williams employs. To be clear, Lehman’s catalog didn’t exist during my formative years but my mind and personal notes on Star Wars’s score (among others) looked quite similar. And as you can tell, functions a bit like that catalog, being a list and analysis of things that comprise my own Style, just for outfits instead of compositions. But I guess they really are the same thing , at least for me!

The key to Cinematic Dressing is to base your expressive decisions around an identity. It can be broad or specific but the idea is that it should have some sort of a POV or framework that is ripe for variation. It’s not about doing a truly fresh character every time but rather about achieving something consistent, not unlike a Theme or Leitmotif in a piece of music. I certainly have multiple POV-character-themes but if you look at the outfits I wear everyday, these Themes pop up constantly, with each “new” fit being a development of that particular identity.

Like Williams, Debney, and other composers, I tend not to default and simply copy-and-paste. To be clear, this isn’t done to be avoidant. Instead, Non-repeats happen in a way that naturally lends itself to variance. I just can’t help making “new” outfits! Each interpolation arises based on narrative direction, though with film score, this is provided to you through the movie itself; for clothing, I simply give myself the prompt.

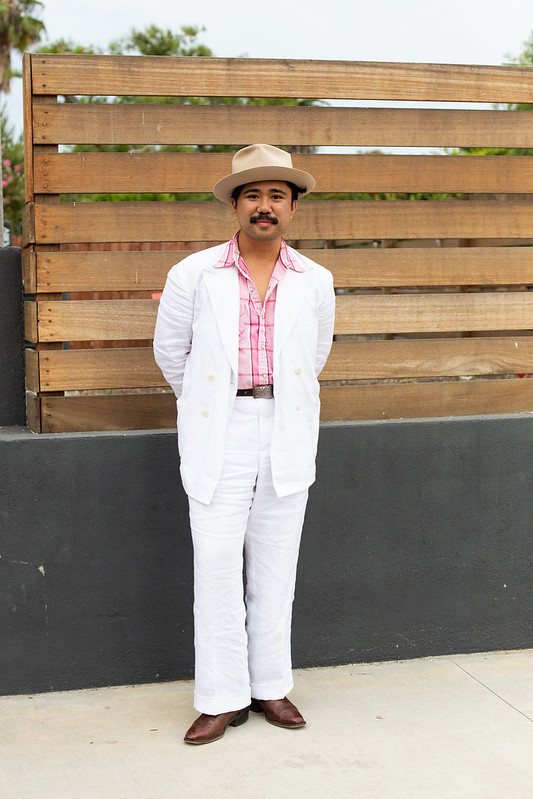

Sometimes Ivy is done straightforwardly, with khaki chinos, repp stripe tie, and a navy blazer. But perhaps it goes rugged with hearty jeans and paraboots or it gets casual by pairing an OCBD with wide legged pants and sockless loafers. Maybe the cowboy dresses up for Church. Frasier or a guy in 1976 might go out for drinks or a date. Maybe the Artist is out for errands!

Looking back, it seems I have recurring POVs that I rotate between, almost like a catalog of Leitmotifs. And just like with Williams and his variations, the base thematic identity of each “character” is still there amogn each outfit. Those “intervals”are still a discernible representative of a particular character, even if I employ some augmentation or change “instrumental voicing”. Granted this helps by having a large wardrobe, but hey, my favorite composers are considered “maximalists” after all— my favs tend to utilize the whole orchestra and certainly make leverage the expressive merit of music theory. And even though may be perceived like it takes a lot of effort, it really is all just instinct at this point. The hope is that it all feels natural and easy going!

I also hope that each outfit with its individual “themes” still retains my Soul-of-sorts, much like how the varying scores of Indiana Jones, Lincoln, and Sabrina are all clearly John Williams even if the notes that make up each film’s themes are all quite different. It’s all about the mindset, the approach and technique. That’s why I see having a discernible and consistent technique across various expressive intentions as a defining feature of Personal Style. [What a mouthful.]

I’m not a fan of John Williams, Film Score, and Classic Menswear because they’re “old school” or nostalgic. No, I love them because they are a playground for and tend to rely on Consistency and Development. It doesn’t have to be as serious as high-art but it can still utilize similar ideas and can be taken just as seriously by a work’s creator (or dresser). It’s just so interesting to me to find the nuance in expression and execution, even if it’s largely unnoticed by the audience. None of this extra effort or attention is “necessary” in the slightest, but that’s what makes all of it fun and worth doing!

So even though I never pursued Composition in a professional manner as well as only tend to compose one piece a year, I still get to have my fun with Thematic Development. It’s just done through the absurd medium of making my little outfits. 😛

Thanks for reading! Don’t forget that you can support me (or the podcast) on Patreon to get some extra content and access to our exclusive Discord.

Always a pleasure,

Ethan M. Wong (follow me on IG)

Big thank you to our top tier Patrons (the SaDCast Fanatics), Philip, Shane, Henrik, and Alexander.

2 comments